Children’s book writer/illustrator/artist Tomie de Paola died this week. His books and his art are deceptively simple, unfailingly gentle, and unspecifically spiritual.

Several years ago, I spent an afternoon with Tomie and his partner/business manager at their home in New London, NH. I’d been assigned to write a profile for a local magazine. It was an amazing experience. In honor of Tomie’s passing, I’m posting my profile in this space (which has otherwise been dormant since 2011, as my life has gone through many changes).

Here you go.

A Very Lucky Man

The Life and Art of Tomie de Paola

By John Walters

“I love Christmas. It’s my favorite holiday.”

If you visit Tomie de Paola’s New London home at this time of year, you’ll see just how true that is. The prolific writer and illustrator loves to surround himself with the stuff of Christmas. “I read once that Christmas is the artist’s feast day,” he explains, “because it’s when the invisible became visible.”

His celebrations have been toned down in recent years, due to a late-in-life case of common sense: “I used to go all-out and just have thousands of dollars worth of poinsettias, and then it was like, ‘I’m not a department store.’ I decided to try to be a little restrained,” he says.

But Tomie’s restraint is another’s extravagance. The living room is dominated by a giant tree full of paper roses, a remembrance of his early years as a struggling artist. In his entryway there’s a smaller tree covered with ornaments he designed himself. There are still plenty of poinsettias around. Plus there’s his massive collection of folk art from around the world, with Christmas-themed items on display at holiday time.

Oh, and there’s a stunning rendition of the Madonna and Child, a large painting in a recognizably Tomie style with strong hints of a late-Matisse influence that he’s happy to acknowledge.

(If you wonder why I call him by his first name, well, that’s what everybody calls him. He’s Tomie, pronounced “Tommy.” He signs his artwork “Tomie” with a heart dotting the letter “I”. There’s no room for formality in his genial, approachable personality.)

His love of Christmas is also reflected in his books. He’s published dozens of stories on holiday themes, including his latest, The Birds of Bethlehem, a gorgeously illustrated telling of the Nativity from an avian point of view. It’s an example of Tomie’s gift for finding a new way to tell an old story.

A master of his genre

At age 78, Tomie has lived a life of accomplishment. He’s one of the masters of children’s literature. He’s published somewhere close to 250 books. He’s won the Caldecott Honor for illustration, the Newbery Honor for writing, and the Laura Ingalls Wilder Medal, a lifetime-achievement award that’s only been given to 18 people. And he’s won the Sarah Josepha Hale Award — the only children’s book writer to do so.

Ask him which honor means the most, and he’ll mention something humbler but more lasting. In 2011, his hometown of Meriden, Conn., named its children’s library for him. “Which is,” he notes with a chuckle, “while I’m alive, really saying something.”

Of all his characters, the most beloved is perhaps the most unlikely: Strega Nona, “Grandma Witch” in Italian, the wise old woman in a small Italian village. “When I wrote the first Strega Nona book, I had no idea that she was going to have this life of her own,” he says.

In fact,, when he first created Strega Nona, he had no idea it would lead to anything. Back in the early 1970s, he was teaching art at Colby Junior College (still a women’s school, not yet named Colby-Sawyer). One day, during a faculty meeting, he was killing time in the usual manner. “The administration thought I was taking notes,” he recalls. “I was, as usual, doodling.” And out came the profile of an older woman wearing a headscarf; he scribbled the words “Strega Nona.”

He’s written 11 Strega Nona books so far, and is rather amazed at what his humble doodle has become. “We did some publicity stuff where an actress dressed as Strega Nona has gone to bookstores, and children just run to her and love her so much! The actress who plays her says it breaks her heart when an appearance is over and the kids are saying ‘Don’t go, Strega! Please don’t go!’”

The swimming duck

The hallmarks of Tomie’s style are simplicity in art, and honesty in story. “Honesty is the most important,” he says. That principle can be seen in his 26 Fairmont Avenue books, a series of chapter books about his own childhood. “I try to tell it as it actually happened. I want children to know that I wasn’t a good boy all the time. In one book, I deal with this other boy who laid in wait for me every day and beat me up!” In future books, Tomie will write about life on the home front during World War II.

As for simplicity, “I don’t want my art to be difficult to look at,” he says. “I have chosen to put my energy into books for children, and I want children to be able to decipher the art with ease.”

But for an artist — as for the duck that’s calm on the surface but kicking furiously underneath — simplicity isn’t easy. Tomie is a trained, skilled artist who can comfortably discuss the intricacies of modern art.

“When I was right out of art school, I was hot to go. I was going to change the world! But it took me a while, to grow not only as an artist but as a person, to become more mature. And then the time came when I could unlearn what I’d learned.”

When he was younger, he adds, “I never really understood Matisse. I didn’t understand the simplicity that he was able to engender. And since that’s what I do myself, I know how difficult it is. But the whole purpose is to make it look easy.”

A youthful dream comes true

“When I was very young, I knew I was going to be an artist when I grew up.” And Tomie’s parents encouraged him. “When I said I’m going to be an artist, they said, ‘Okay, we’ll get you art supplies so you can practice.’”

And his mother gave him a love of books and reading. “My mother read aloud to me every night,” he recalls. “I was a rather difficult child. I didn’t go to sleep; I didn’t want to miss anything. But I did love my mother reading to me.”

She was also a sucker for traveling encyclopedia salesmen. “I always thought we had a secret ‘X’ on our door: ‘That lady will buy the books!’ We ended up with three sets of encyclopedias. And I used to sit and read them, from A to Z, because I just loved reading. And I still do!”

Tomie got his formal art training at the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, N.Y., and went on to the inevitable next phase — starving artist — by way of a monastery. “I wanted to be a Benedictine monk,” he says. He entered the Weston Priory in Weston, Vt., but “I lasted about six months, max.”

Then came the “starving” part. “I lived in a little old farmhouse. I started doing Christmas card designs for a woman who had a business in Pittsford, Vt. She kept me in Spam and coal, so I could eat and stay warm.”

This was where the paper roses came in. “I had absolutely no money, but I had 88 acres. So I cut down a tree, and I made paper roses. Paper roses have always been on my Christmas tree since then.”

A showing of his art at a Boston gallery led to a career as an art teacher — in Boston, San Francisco and finally in New Hampshire at Colby-Sawyer College and New England College.

Teaching gave way to full-time writing and illustrating when, one day, he received a royalty check from his publisher that was bigger than his college paycheck. “I always enjoyed teaching,” he says. “But to have that dream come true. You know, it’s a wonderful thing to make your living doing what you really want to do.”

Home base

“My house is an extension of myself as an artist and a person,” he says, sitting in a big white-walled open room that he designed himself. The room, like the rest of the house, is full of items from Tomie’s extensive collection of folk art and decorative objects — “the things that I love,” he says. There’s a bit of a Southwestern feel to the room, because of the spare white walls and the many Mexican and Native American objects displayed on built-in shelves.

The rest of the house has a different feel, although the two parts somehow work together. “This was the original Yankee Barn home,” he says. Tomie bought it from the late Emil Hanslin, founder of Yankee Barn Homes. The barn-turned-studio next door was the original office space of the company, now headquartered in Grantham. Tomie’s house and property are located almost literally a stone’s throw from Main Street in New London, but it feels much more secluded. He owns 14 acres of land, some of which is used as a cornfield by Spring Ledge Farm. In return, he says with obvious relish, “I have picking privileges!”

We take a walk across a courtyard to Tomie’s office and studio. This is where his partner, Bob Hechtel, handles the business side of the operation, and where Tomie makes his art. The studio has an incredible array of art supplies of all kinds; Tomie calls it a necessity. “Living in the country, you have to buy in bulk,” he says. But one also gets the impression, from house and studio, that Tomie feels most at home when he’s surrounded by a bounty of well-organized, beautiful, purposeful things.

A lucky man

“I’ve always said that I was very lucky,” Tomie says. That even applies to growing older. His creative pace has slowed, matching a decline in the publishing business. “Sales aren’t like they used to be,” he says. “That’s a worrisome thing. We had a meeting with my publisher, who told me, ‘We don’t know what’s going on.’ I don’t think anybody has any idea where this electronic revolution is really going to take us.” He acknowledges a certain sense of relief that the bulk of his career occurred before this age of uncertainty.

His own future nearly came to an end just before Christmas 2011. At the end of a busy book tour, “I had some serious and mysterious health issues.” He was hospitalized for most of December. They never figured out exactly what the problem was, but he did recover. Now, he’s looking forward to writing and making art for as long as he can, and celebrating as many Christmases as he can.

As he approaches his 80th year, Tomie can look back on a career that could hardly have gone better. “When I think of where I’ve gotten, I’m humbled by it,” he says. “To be an artist, to have some of my books in print for 25 years or more and they’re still in print, they’re still selling. That’s my immortality, you know. When I realize that these books will outlive me, I’ll never die as long as my books are in print. And that’s very, very mind-blowing for me.”

So yesterday, I drove from Montpelier to White River Junction, VT, about an hour away. (Great meeting with ceramic artist Eric O’Leary; may lead to collaboration on a book project.) All well.

Then this morning I get up to give my wife a ride to the bus stop, about three miles away. And when we’re almost there, I get a flat tire. In the middle of downtown, right outside the Uncommon Market, which has great coffee and tasty breakfast sandwiches.

Wife walks three blocks to the bus. I whip out the cellphone and call AAA, then go in the Market and have breakfast. Sit on a bench inside the Market, looking out the window at my car.

About the time I finish my coffee, the tow truck from Bob’s Sunoco pulls up. He hoists my car on his flatbed and drives it (and me) to my usual repair shop, AutoCraftsmen.

Pardon the product placements. It’s not that I’m getting any kickbacks; I just appreciate all these businesses. Great service, nice people.

A few minutes before 8, they open up for the day. They’ve got a full schedule, but they sneak my car in first. Now, I should explain that my car is 14 years old and has 280,000 miles on it. It has a full-sized spare tire is mounted outside on the rear hatch. The tire’s been sitting there, untouched, since the car was new.

The mechanic takes it off, and — mirabile dictu — it still works! It holds air, the rubber hasn’t turned to dust. And I drive home. The whole experience cost about an hour and a half of my time; I had a nice breakfast while I waited; the tire had the decency to not go flat while I was on the freeway yesterday; and, to top it all off, I already had an appointment the day after tomorrow to put the snow tires on the car, so I don’t have to worry about new tires until spring.

If you ever have to have a flat tire, I strongly recommend that you do it exactly this way.

Did a talk tonight at a library. Audience: 1. One. Singular.

Well, the library director was there for part of it. But one person actually, voluntarily showed up to hear me talk.

I didn’t sell any books. I gave one to the library. I drove almost three hours each way to get there.

Fail?

Yes. And, well, no.

See, my talk centers around the work I’ve been doing — in radio and print — for the last decade-plus. I’ve spent most of that time telling the stories of interesting people. People of all kinds. The main point I hope to make: there are interesting people everywhere, in every community, neighborhood, and family. Indeed, I contend that everyone has a story worth telling, worth preserving, worth celebrating.

Now, in my book (Roads Less Traveled: Visionary New England Lives, Plaidswede Press, available at many bookstores in New Hampshire and Vermont or through my website, thanks for asking), I tell the stories of a couple dozen people: some of the most interesting people I’ve come across. I felt that their stories were especially worth telling at length and preserving in print.

But although these people have had exceptional lives in one way or another, my broader point remains. Everyone has a story to tell.

So I give my talk, which includes brief excerpts from the book. One of them was the story of David Krempels, a man who survived an incredible personal tragedy: on the first day of his honeymoon, a large truck smashed into his car. His wife was killed; he was left with a severe brain injury. He was plunged into a nightmare of poverty and loss. Three years later, he won a lawsuit over the crash. The award made him an instant millionaire. And he used a good chunk of the money to create a foundation to help people with brain injuries.

After my talk, I had a brief chat with my “audience.” She told me that Krempels’ story had resonated with her, because she herself had suffered an illness that almost completely disabled her for a considerable period. She had recovered, but the experience had left its mark.

That was straightforward enough. But she had also taken in my broader message, that we all have a story to tell. And I sensed that she may have seen her own life story as something worth telling or even celebrating.

Not that she needed my validation. But if I gave her a bit of fresh perspective on the value of her own experience, then it was not a failure, not in the least.

“Be not forgetful to entertain strangers; for thereby some have entertained angels unawares.”

–Hebrews 13:2

Yes, the competition is very stiff, but I think I’ve picked a winner: the animated spot for Abilify, the antidepressant medication. Or, to be more precise, the “add-on treatment when an antidepressant alone is not enough,” as the Abilify website puts it.

Now, commercials for prescription drugs tend to be high in creep factor, if only for their invariably lengthy lists of possible side-effects. And commercials for antidepressants tend to be among the creepiest of this very creepy lot. But this Abilify spot… geez. It’s in a class by itself. The ad is animated in a very pleasant style which is, to me, faintly reminiscent of Charles Schulz’ work in Peanuts. But the content and the messages would have ol’ Sparky spinning in his grave.

As in every other antidepressant commercial, the sufferer is female. (The only exception to this rule: if an ad depicts several patients, there will be a token man or two among all the women.)

A friend of mine pointed out that when an ad is aimed at women, the product is meant to solve a problem or relieve an anxiety. Or, even better, create an anxiety and provide a solution. If an ad is aimed at men, the product is said to make their lives even better than they are. See, men don’t have any problems.

The Abilify spot also includes another standard reinforcement of gender roles: the female sufferer is rescued by a male doctor. Wearing a white coat. Usually with a stethoscope dangled around his neck. Because, you know, that’s what doctors do. All this is offensive enough, but there’s a whole lot more going on in this 90-second-long Abilify ad.

When I’m watching TV and the ads come on, I usually hit the MUTE button. Somehow, the absence of a soundtrack made the Abilify commercial even more compelling and disturbing. So I’m going to take you through the ad, focusing almost entirely on the visuals. My comments are in italics.

I realize that I’m going to be rather obsessive about the details of this ad. In my defense, I’d point out that advertising is a high-stakes enterprise and that every little detail is meticulously planned out.

A woman, in early middle age, is standing outdoors. Green ground, light blue sky with scattered puffy clouds. She is wearing an olive-green top, blue skirt, and black low-heeled shoes. Her eyes are widely spaced and almond-shaped; almost Asiatic, although there is otherwise not a hint of the Orient in her. In fact, aside from her eyes, she looks thoroughly middle American. She has a wan smile on her face.

Of course it’s a woman. If antidepressant commercials are taken at face value, 99% of depression sufferers are women. Medically speaking, this is nonsense. But it’s the picture we’re shown, over and over again.

Then a hole opens in the ground to her left. She frowns at it, as two heavy-lidded eyes appear in the hole.

She doesn’t move. A hole is opening inches from her foot and some kind of creature is inside. She frowns, but doesn’t move. Is she resigned to her fate? Is she really, really stoic? What?

The hole widens. She takes a single step back, just beyond the edge of the hole. Her frown turns to an expression of sad resignation. A black shapeless body emerges from the hole.

Since she’s not making any moves to escape or fight, we must conclude that this bleak creature is familiar to her. To me, it looks like a sleepy younger cousin of the black oily thing that killed Tasha Yar in Star Trek: The Next Generation. I’d run away; but maybe that’s just me.

A legend sppears on the screen: “ABILIFY [brand] (aripiprazole) treats depression in adults when added to an antidepressant.”)

So what the hell does “treats depression… when added to an antidepressant” mean? I thought that’s what the antidepressant was for. Well, maybe it makes sense. But I checked Wikipedia’s entry for Abilify; it reports that the drug has been approved by the FDA for four different conditions: schizophrenia (2002), certain symptoms of bipolar disorder (2004), an adjunct treatment for depression (2007), and to treat irritability in autistic children (2009). Looks like the drug company is trying anything it can to find new uses for one of its patented drugs. This is where a lot of Big Pharma’s frequently-touted research spending goes: not in the hit-or-miss search for new drugs, but in the effort to find new uses for drugs already FDA-approved and still under patent. The classic example of this is Rogaine, the treatment for thinning hair, which began its life as a blood-pressure medication.

The creature morphs into a sort of vertical black cloud, and then expands into a black balloon with a string beneath. The woman takes the string.

Acceptance of a tragically flawed existence?

The string changes into a chain, the “balloon” into a weighted ball. It falls to the ground as she hangs on. She has a pained smile on her face. Then she pulls on the chain, lifting the ball. It arcs over her head and plunges into the ground, as she gamely holds on to the chain.

Apparently yes, acceptance. She’s not only not doing anything to help herself, she seems more attuned to the needs of this creature than to her own.

A crack forms underneath her, catching one of her feet. She looks down with dismay. She falls into the earth, up to her chin. Then she partially emerges, up to her chest. The hole widens and the creature’s eyes appear in the hole next to her. The ground rises up, beginning to engulf her. She looks at the creature with resignation, tinged by dread.

And again, she makes no move to escape from the creature or the hole that’s forming a cone on all sides of her. This is a remarkably passive person. Guess that’s why she needs drugs.

The creature is equally passive. Sleepy eyes, oozing here and there, disappearing and reappearing. Aha, symbolism! It’s a manifestation of her depression.

A male figure approaches from stage right. He’s wearing brown shoes, brown pants, a blue shirt with red tie and, yes, a white coat. He’s in late middle age, has almost no hair, and wears glasses. The creature glances at him and recedes into the ground. The doctor’s smile has a bit of smirk in it. He reaches a hand toward her; she smiles at him.

Of course it’s a male doctor in a white coat. In drug advertising, maleness and a white coat are the universal signifiers of superior knowledge and wisdom.

She takes his hand. He helps her up, as the creature looks on from the far side of the hole.

Nope, a woman couldn’t possibly get out of a predicament without the help of someone with a penis.

A legend appears on the screen: “Some people had symptom improvement as early as 1-2 weeks.” The doctor folds his arms, still smiling; the woman looks back toward the hole, which rises from the ground and becomes the creature. The creature becomes airborne, floating beside her; she smiles at it. Then she folds her arms and looks sternly at the creature, which recoils and shrinks.

Already, the penis is working its magic.

The scene changes. The doctor pulls down a filmscreen, which is showing the Abilify logo. The woman is sitting in a chair facing the screen, writing notes on a clipboard. There’s a second chair next to hers; the creature is sitting there with its own clipboard, taking notes. The Abilify logo is replaced on the screen by the figure of the doctor, who is speaking. Meanwhile, the “real” doctor is looking smugly at the woman who is watching the movie image of him.

This may be the low point of the entire ad. Good God, talk about narcissism. The doctor can’t be bothered to actually talk to the woman; instead, he makes her watch a film of himself. Bleccch. Creepy.

One note about the soundtrack here. Most of the ad is narrated by the woman, describing her condition. For the “informational” part of the ad, the stuff about contraindications and people who shouldn’t take Abilify. the voice is provided by a calm, collected male narrator. Of course.

The view shifts to the creature and the woman, side-by-side, each taking notes. The woman brings the pen to her mouth, then continues writing.

Me and my depression, strolling down the avenue. I don’t know what’s worse: the woman’s acceptance of the creature as her companion, or the creature’s willing participation in its own defeat.

Check that: I do know what’s worse. It’s the woman’s acceptance.

The scene changes. A hilly landscape in the background, a mostly cloudy sky with a few bits of blue showing through. The woman walks in from stage left, smiling, and carrying a folded blanket. She is now wearing a pink top with the blue skirt.

Amazing. Abilify will not only lift your mood, it will spiff up your wardrobe.

The creature floats into view behind her.

I suppose I should admire the restraint shown by Bristol-Myers Squibb. They’re not claiming that the drug will banish depression, just bring it under control. Temporize it just a bit. But still, the idea that the woman has to passively accept the constant presence of a nightmare creature… I shudder.

And, of course, the subtext is that you’ll need to keep on taking Abilify indefniitely. Because if you stop, the creature will be reenergized and you’ll plunge back into the earth. So keep that cash flow coming, ladies!

Then comes a man — presumably her husband — walking with a walking stick, a thin smile on his face. She motions to him, to follow her.

Behind the man, a girl emerges; a young smiling teenager with hair tied behind her head. The woman, the creature, the man and the girl — in that order — move across the screen.

Do they not see the black, heavy-lidded creature? (In which case, I guess it’s a figment of her imagination visible only to her and her full-of-penisy-wisdom doctor?) Do they see it, and smilingly accept it as part of the family? Either way, ick.

The scene shifts a bit. They enter a flat open area with a pathway going just behind them and winding up a distant hill. There are two figures in the far background. The man is now seen to be carrying a picnic basket. The creature moves behind the woman to her right side.

The woman unfurls the blanket and spreads it on the ground. A wide path, just to their right, leads off into the distance behind them. The woman and girl sit down on the blanket. The creature hovers to the woman’s right. The man sets down the picnic basket and sits on the blanket.

It’s hardly a family picnic if you don’t bring along your amorphous black creature. Also, another soundtrack note: as the family prepares for its picnic, the male narrator is reciting a list of possible side effects. So you see the happy family outing, and you hear “dizziness, seizures, impaired judgment,” etc. This is a presumably deliberate juxtaposition of physical peril with warm fuzzy visuals, most likely an attempt to soften the impact of the mandatory warning.

The scene shifts. Closeup of the woman speaking directly into the “camera” with a serious look on her face. The creature hovers over her shoulder.

Just me and my shadow…

The scene shifts back to take in the landscape, with the family and creature in the foreground. Then the creature dips down into the ground, turning into a hole with eyes.

Oooh, shape-shifter! My creepy-meter just pegged again.

The hole/creature moves from behind the woman to right beside her. A pair of blue stripes (part of the Abilify logo) covers the wide path. The woman reaches for the picnic basket.

The scene disappears, replaced with the Abilify logo, website, and toll-free number. The end.

This may seem a rather excessive takedown for a television ad, when it’s practically in their nature to be at least a little bit creepy and annoying. But there are three reasons why Abilify impelled me to get out my rhetorical elephant gun.

First, the advertising industry devotes tremendous resources to propping up gender stereotypes in order to create market niches for an endless array of products, from probiotic yogurt to pisswater beer and from gaudy jewelry to foul aftershave. These ads have a tremendous cumulative effect beyond the simple moving of product; they also make people believe that they need to conform to stereotypes. When, in fact, most people are naturally somewhere in the middle. Yes, there are differences between men and women; but they are far less dramatic than commonly depicted in advertising. In reality, the Venn diagram of “Men” and “Women” has a whole lot of overlap. There are plenty of men who like to dress nice and listen to opera, and plenty of women who change their own oil and watch football.

Second, Big Pharma spends an unconscionable amount of money on direct consumer advertising. I have no idea how much, but I’ll bet it dwarfs their constantly-hyped research budgets. This is money that does not need to be spent. It is WASTE in our health-care system. People complain a lot about waste, fraud and abuse in government; I contend that there is a whole lot more waste, fraud and abuse in the private sector. Prescription drug advertising is just one example.

Third, advertising prescription drugs to consumers is fundamentally inappropriate. The average consumer has no basis for judging the veracity of a drug ad. Doctors have the necessary expertise. (Well, that’s their assigned role, anyway.) When drug ads work, two things happen: Doctors get hounded for unnecessary prescriptions, and health-care dollars are spent on costly patented drugs as opposed to generics, which are often just as good or even better and are ALWAYS much cheaper.

There: the creepiest commercial on television. I rest my case.

Just a quick update for the millions who are breathlessly following my sleep apnea saga. I’ve had my CPAP machine for a couple of weeks now (see previous posts for more info). And after a few rough nights, I’ve adjusted reasonably well.

It’s still not exactly comfortable to fall asleep with a plastic mask blowing air into my nose, but it’s okay. I do manage to sleep through the night.

As for the onset of brilliance and productivity… I can’t say it’s happened. No particular evidence that I’ve suddenly become a genius or anything. Just a writer guy slogging along. And I’m still hoping that I’ll be able to wean myself from the CPAP, as I continue to lose weight and get in better shape.

So. As with many things in life, no climactic moment or life-changing experience. We go on.

(This is the first of three essays on the state of public radio. The second will look at the consequences of public radio’s recent successes. In part three, I will offer some ideas for a more relevant, vibrant public radio. As someone with nearly 20 years of experience in the field, I think I have some insight to offer. Hope so, anyway.

Previously, I wrote “There Is No Spit in Cremo!” which discussed the original concept of radio as a public service and its rapid descent into commercialism. In an attempt at drollery, I dubbed that essay “part zero” in the series.)

Back in the 1940s, all the big commercial broadcasters were on AM radio. Hard to imagine, I know. FM radio was in its infancy, it had very few listeners, and no one yet realized its potential as a superior broadcast medium. That didn’t happen until the late 1960s.

So in the ’40s, when the government set aside the lower end of the FM dial (from 88-92) for “educational” broadcasting, commercial broadcasters didn’t really care. Without that decision, we wouldn’t have any kind of public radio today; FM “real estate” is far too valuable to let any of its profit potential go to waste.

For its first couple of decades in existence, “educational broadcasting” was largely a backwater. Most licenses were held by colleges and universities, and operated in accordance with their educational mission. They didn’t really care how many people listened. And relatively few did. The bulk of the programming was classical music.

This began to change in 1970 when National Public Radio was established. The following year, NPR created All Things Considered, its afternoon news and information program. In 1979, Morning Edition went on the air. Those programs attracted an audience eager for serious news on the radio, and soon displaced other offerings from the prime hours of radio — “drive time,” roughly 6-8 a.m. and 4-6 p.m. Those are the peak ratings hours for all radio stations.

My own broadcasting career began in the mid-1970s, when I was a student at the University of Michigan. A couple of internships at the university’s public radio station led to a part-time job after I graduated.

At the time, Michigan Radio was a congenial place to work. Staffers received generous pay and benefits, and were given wide latitude in doing their jobs. A few seized the opportunity and did some unique, exciting programs. Some, on the other hand, became too comfortable. They did minimal work, churning out pretty much the same stuff every day.

But the biggest force for change was Ronald Reagan. When he became President, he made large cuts in funding for public radio and television. This forced local stations to become more entrepreneurial, seeking funds from listeners, corporations, and foundations. This meant that they had to pay more attention to their audience.

Michigan Radio was hit from multiple directions. The energy crisis of the late ’70s delivered a big blow to the US auto industry, and hence to Michigan’s economy. All three of Michigan Radio’s major funding sources — federal, state, and University — were cut at almost the same time. In the ensuing budget crunch, several staffers were laid off. Including me.

The Reagan cutbacks, along with the early success of NPR’s daily news programs, set public radio on the course it has followed to this day. Stations needed listeners. The number-one attraction: NPR. From the early 80s onward, public radio gradually shifted away from music and cultural offerings and toward news and information. Also, away from local programming and toward higher-quality, higher-cost national programming.

This trend accelerated in the early ’90s, when NPR launched a full weekday schedule of news and information programming. The consistent format was an attractive proposition for stations that were hamstrung by mixed schedules of news and music: every time a station shifted from one to the other, there was an almost complete turnover in the audience.

This was a huge problem for stations becoming ever more dependent on donor support. The magic words for public radio fundraising are “time spent listening” (TSL). If you listen more than a certain number of hours per week (roughly 8-10 hours, last time I checked), you are very likely to donate. If your TSL is lower, you are very unlikely to give.

If a station wants to boost audience and TSL, a consistent format is a must. Since the news format was invariably more popular than music, the choice was clear.

Through the 1980s, Michigan Radio gradually, and rather grudgingly, adjusted to these new realities. But its finances continued to erode, eventually reaching a critical stage. In 1995, new management was brought in. The following year, most of the old staffers were let go and the station dropped classical music in favor of NPR’s news and information schedule.

I had rejoined Michigan Radio in 1993 after several years in commercial radio. I was, I believe, the only on-air regular who fully survived the 1996 transition to the new format. I stayed there until 2000, when my wife and I moved to New England.

Meanwhile, commercial radio had virtually abandoned any kind of news and information programming. Most commercial stations don’t even pretend to offer any news. Even the so-called “news” stations do little or no original newsgathering; their news departments largely consist of anchors, ripping and reading copy from the Associated Press or lifted from newspapers and websites. Into this massive breach stepped NPR, offering high-quality news that towered above the meager efforts of commercial stations and networks. NPR had a clear field. And it was a very fertile field; news listeners tend to be well-educated, affluent, and inclined to become donors.

In many markets, public radio stations are very competitive in the ratings race. In some markets, the public station is actually #1. And thanks to the affluence and loyalty of its audience, public radio has become a fundraising powerhouse — especially in large markets. Most public radio stations have become highly professionalized operations, becoming more and more separate from their roots in higher education.

Public radio has done (and still does) wonderful things. It provides an absolutely unique service to our social dialogue and our political system with its serious and objective news coverage. By and large, it has used its success wisely, making significant investments in its programming. It has also done better than many traditional media outlets in adjusting to the Internet age, providing supplemental material to its broadcast offerings and plenty of original stuff as well. This is, in most respects, a golden age of public radio.

But success has its consequences. I’ll explore those in the next installment of this series. Stay tuned.

If you were going to make a low-budget movie, you might not think of science fiction as the most promising genre. But Stephen Maas saw it another way: “I was interested in telling a story that took place in as few locations as possible, because we had no money.”

So, how about the interior of a spaceship? And a story that focuses on the human hardships of a mission gone badly wrong? Well, that’s Tin Can, a full-length film made by a small group of Vermonters. And despite its minuscule budget, Tin Canis a compelling story that’s very well told.

![TC Composite v14 corrected credits-1.avi_snapshot_00.26.56_[2011.06.10_14.38.17]](https://johnswalterswriter.files.wordpress.com/2011/08/tc-composite-v14-corrected-credits-1-avi_snapshot_00-26-56_2011-06-10_14-38-172.jpg?w=497&h=276)

The crew: Alan Kenneth (Jayson Argento), Peter Bennett (Stephen Maas), and Mark Riley (Eric Clifford)

Somehow, he missed “key grip.”

Oh, one other thing: The movie’s primary set was built inside his one-car garage. “Actually, the first thing you told me was that you were building a spaceship in your garage,” said Logan Howe, who joined the project after that intriguing intro. (Well, “joined” is a mild word for her involvement; she was the film’s director, set designer, art director, carpenter, and one of the actors, among many other things.) “Yeah,” replied Maas, “that was the hook to get people to help for no money — ‘Dude, there’s a spaceship in my garage!'”

I got to meet Maas and Howe in late June, when I was guest hosting The Mark Johnson Show on Radio Vermont/WDEV. (The quotes in this post are taken from that interview.) In preparing for the interview, I got to see a movie that hasn’t officially been released. Yet.

And it was a captivating watch. Tin Can follows three men who set off on a two-year-long mission to Mars. After many months in their small craft, they begin to show signs of strain. Then come a series of equipment failures and accidents that put their survival (and their sanity) at risk. Finally, there are questions about the nature of their mission and what, exactly, is really going on.

The premise of Tin Can is based on real science — in particular, aerospace engineer Robert Zubrin’s proposal for a (relatively) low-cost, simple manned mission to Mars. “This is a real mission design,” said Maas. “We could do it tomorrow.”

The film’s intensity is greatly enhanced by Howe’s set design — a masterpiece of minimalism. She called the design “a spectactular challenge that I pored over for two weeks.” The cramped quarters reinforce the isolation of the voyagers — and the dangers they face when things go wrong. “I’d envisioned the set in pieces like a conventional one,” said Maas. “But Logan insisted on making it a real space that was completely enclosed.”

Good call.

Tin Can isn’t always an easy film to watch; its emotional intensity is downright scary at times. What I hadn’t realized, until the interview, is how much of that intensity was all too real. At one point, the astronauts are forced to take refuge in their bunks — small, completely enclosed “pods.” When it’s time to come out, Maas’ character (mission commander Peter Bennett) is trapped in his bunk. Try as they might, his crewmates can’t get the door open. Bennett is imprisoned in that tiny space for months and months. Eventually, he goes insane; in a particularly harrowing scene, Bennett rages at his crewmates and begs them to release him.

“I’m claustrophobic in real life,” said Maas. “It’s one of my worst fears. I’m 6 foot, four inches tall; the bunk was only seven feet.”

So he had to control his real-life terror while at the same time, exploiting it for the sake of the movie. “That was one of the most stressful days on the set,” said Howe. “I hated putting him in that position. I think we even had a ‘safe word’ if he had had enough.”

That’s real commitment. And it shows in the final product, a remarkable piece of work by a team of very talented people.

As of this writing, there are no scheduled showings of Tin Can. The next move is to send it to potential distributors and submit it to film festivals; many of them will not consider a movie that’s already been shown publicly. “We will show it eventually,” said Maas. “One way or another, we will insist on showing it locally. We’re hoping a distributor will do so, but we’ll do it ourselves if necessary.”

I’d advise you to be on the lookout for Tin Can. I’d like to see it again myself, this time on the big screen of a theater instead of a TV set at home. I imagine the intensity would only be that much greater.

You can keep up with the film at its website, or follow its Twitter feed or Facebook page. And if you’re so inclined, give them a donation in support of their publicity and distribution efforts.

Day Three of the CPAP experience, and boy am I tired. Been trying to sleep — and mostly failing — with this lovely mask thing on my face. Last night, after lying there for at least a couple of hours, I took the damn thing off. Which kinda defeats the purpose; I can’t really expect the CPAP to prevent sleep apnea if it’s turned off and the mask is lying on the nightstand.

They told me I’d get used to it. They said I’d notice a big difference in my quality of sleep, and in my alertness during the day. Of course, sleep doctors, nurses and technicians seem to be good at delivering reassurances that turn out not to be so true. Yeah, it’s too soon to give up… but I sure hope I start feeling comfier soon, or I’ll be pulling the plug on CPAP and taking my chances with apnea. (Well, what I’m really hoping is that I will continue to lose weight and gain fitness, and remediate my apnea the natural way. I’ve lost at least 15 pounds this year, and I’m on a good program.)

The good folks who design CPAPs have actually done a very good job making them as flexible and comfortable as possible. But it’s still fundamentally unnatural to sleep with something clamped to your face. I imagine some people adjust better than others; myself, I am slightly claustrophobic, and I think that’s making it harder for me to cope.

And if I may be permitted to whine a bit more, the CPAP has taken one of the great joys of my life and filled it with anxiety. I like being in bed; I like sleeping. Especially since I get to sleep with someone I care about and appreciate. But this mask is overshadowing the whole sleepytime experience, and that sucks.

So… sorry, folks. I haven’t written the Great American Novel or cured cancer or devised a debt-ceiling solution acceptable to both Rand Paul and Bernie Sanders. In fact, I’m struggling to be even minimally productive after three nights of very little sleep.

But hey, at least I’ve written a blogpost. Can I go take a nap?

Oh boy, oh boy, it’s here! My shiny new CPAP machine — the marvel of medical technology that’s going to change my life! And make me look like an alien for eight hours a day!

Oh boy, oh boy, it’s here! My shiny new CPAP machine — the marvel of medical technology that’s going to change my life! And make me look like an alien for eight hours a day!

As you may have previously read, I’ve been diagnosed with severe sleep apnea. It’s a breathing disorder involving a blockage of the airway during sleep, which interferes with healthy breathing patterns, resulting in poor sleep quality, fatigue, and difficulty concentrating. It can also lead to more serious medical conditions.

The treatment is this thing I’m wearing: a breathing mask attached to a CPAP machine. The CPAP pumps air (at low pressure) into this mask and hence into me, which helps keep the airway open. I’ve been told by every doctor, nurse, and technician that CPAPs make a marvelous difference in a patient’s quality of life: better sleep, more energy and alertness, etc.

Starting tonight, I get to wear the CPAP while I’m sleeping. So I figure that when I wake up tomorrow, I’ll be a bundle of energy and productivity. By this weekend, I expect to finish and publish my first novel. Which will soon take home a Pulitzer Prize. The Nobel, Oscar, Grammy, and maybe the odd James Beard or Lindenberg Medal* should follow. And no, it doesn’t matter whether those awards will actually be given this month; my newfound genius should overcome such minor obstacles.

(*”For conspicuous service to philately,” as if you didn’t know.)

In anticipation of this encomial flood, I’m clearing space on my mantelpiece next to my 2009 Donald M. Murray Journalism Award and my 1985 Ann Arbor Recreation Department Co-Rec Slow Pitch Softball Friday Yellow Division championship plaque.

So check me out tomorrow, and prepare to be amazed.

Dear Reader: You stand at the beginning of a multi-part blogpost on the state of public radio today. As a longtime pubradio vet (note skilled use of insider jargon), I think I have some perspective and insight to offer.

But first, a few words on How We Got Here. Meaning, how radio became what it is today — an overwhelmingly soulless, corporate entity with a relentless focus on efficiency, absolutely no regard for public service, and virtually no connection to stations’ home communities (except for a very energetic and well-paid sales staff, of course). This is relevant because it has (indirectly) helped foster the current successes of public radio, and helped create some of the challenges it now faces.

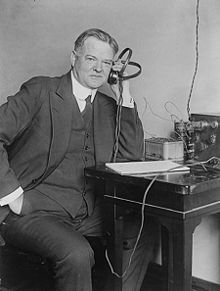

In the beginning, there was a fundamental belief about the brand-new medium of radio: it should be focused on public service, on enhancing the social and cultural life of the nation. As for commercials… well, here’s Herbert Hoover (yes, that Herbert Hoover) speaking about radio in 1922, when he was Secretary of Commerce:

“It is inconceivable that we should allow so great an opportunity for service to be drowned in advertising chatter.”

Herbert. Freaking. Hoover. A man not remembered as a rabid champion of socialism. The guy in charge of regulating radio in the Warren Harding administration, saying that radio should forever be unsullied by crass commercialism.

Well, that didn’t last long. By the late 1920s, radio was booming — and its commercial potential was clear. But the early ads were restrained; no aggressive selling was allowed, no mention of specific prices.

Then came an extremely aggressive businessman named George Washington Hill, head of the American Tobacco Company. Maker of Lucky Strike and Pall Mall cigarettes, and the top-selling cigar in the country — Cremo. Its appeal arose from two factors: a bargain price of five cents apiece, and advertisements that touted its machine-rolled cigars as superior to old-fashioned, hand-rolled cigars. Just imagine, Cremo basically told America, what horrors might unfold in those dank, fetid factories full of dirty, greasy, frequently foreign cigar makers. Worst of all, it was hinted, these guys might just be sealing each cigar by licking the wrapper!!!!! Germs! Lice! Cooties!

Mr. Hill wanted to spend big bucks on radio ads. And he wanted a hard-sell approach, including prominent mention of Cremo’s five-cent price. And he wanted to use that immortal slogan, “There Is No Spit In Cremo!”

By this time, Hoover was President. But the Depression was raging, and Hoover had bigger things on his mind than the suppression of advertising chatter. The CBS network gratefully accepted Mr. Hill’s money. Yeah, the Tiffany Network, home of Edward R. Murrow and Walter Cronkite, made its bones by yelling at America about saliva-tainted cigars.

It wasn’t long before radio was awash in advertising chatter. High-minded principles of service took a back seat to inoffensive, ad-friendly entertainment. Many popular programs were actually produced by advertisers, with lots of commercial mentions built into the program itself. On tobacco-sponsored shows, you can bet that the stars practically chain-smoked through every program and often remarked on the joys of puffing on cancer sticks. Of course, broadcasters didn’t immediately forsake all forms of public service. They often made time for high culture, an uplifting and politically uncontroversial thing to do. One example: for nearly 20 years NBC maintained its own symphony orchestra, considered one of the best in the nation.

As time passed, commercial considerations became predominant. There was just too dang much money to be made! Cultural and public service programming was exiled to marginal time slots, cut and cut and cut again, and eventually eliminated.

Now, consider the broadcast license. Each station had to gain a federal license to broadcast, and each license periodically came up for renewal. The idea was that the broadcast spectrum was a limited resource owned by the public. So renewal was contingent on the broadcaster showing that it had used the license in the public interest.

But in reality, a license is the linchpin of a broadcaster’s entire business. Its investment in staff, equipment, and programming, its access to the money machine of ad revenue, its prestige and influence, all depended on that little sheet of paper from the feds. Broadcasters detested the idea that they could lose everything because of some abstract notion of public service. They fought constantly to make license renewals easier to obtain. And broadcasters are a powerful lobby, since they can provide abundant supplies of a politician’s two biggest needs: money and publicity.

Technically, it’s still true that a broadcast license is a temporary permit to use a public resource. But renewals are virtually automatic; to lose a license, a station owner would practically have to commit murder and broadcast it live. In practical terms, broadcast licenses are private property to be exploited by their “owners” for maximum profit.

Because of the potential for profit, a broadcast license is more valuable as a commodity — a trading card — than as a permit to actually broadcast stuff. It’s like a farm surrounded by subdivisions and strip malls: even if the farm is a viable business, its land is far more valuable than the farm itself. The farmer can make a lot more money by selling the land than s/he could ever hope to realize through a lifetime of tilling the soil.

Similarly in radio. A locally owned commercial station can be profitable, but only through hard work, keen business practices, and (most importantly) a desire to be a broadcaster, not just an investor. Put yourself in the independent station owner’s shoes: do you hold the license and operate a tough but rewarding business at a good profit, or gain an instant windfall by selling to a broadcasting conglomerate?

(There used to be strict limits on station ownership, nationally and within single markets. Those limits have been repeatedly diluted by a Congress strongly influenced by the powerful broadcasting lobby.)

The vast majority of commercial licenses are held by a handful of giant corporations. Their stations are cookie-cutter operations with pre-programmed music formats or talk shows simultaneously airing on hundreds of stations, whose schedules contain little or no local content.

Today, radio is beset by an ever-growing legion of new competitors: Internet radio, podcasts, new media. There are predictions of the death — or at least widespread irrelevance — of radio.

If this happens, new competition will certainly be a key cause. But it’s also true that the radio industry has been its own worst enemy. It has effectively strip-mined the medium, thoroughly exploiting its riches for maximum profit with no regard for the future.

There is still, within each radio license, that great opportunity for service envisioned by Herbert Hoover. The best commercial radio stations of the past (and the few that still remain) were sources of information and culture, and community gathering places — part of the fabric of community life. And yes, they were profitable businesses. Whenever a distant corporation takes over a station, it kills the local programming, cuts most or all the staff, and strips away the license’s hard-won value as a community resource. It’s like a mining company taking the ore and leaving behind a slag heap. Call it intellectual strip-mining.

And in today’s media marketplace, a slag heap of a radio station has very little appeal.

Next, part 1: The rise of public radio.